The Military Communications and Electronics Museum

“A museum is a story,” says Annette Gillis, Curator at the Military Communications and Electronics Museum, a Kingston museum that specifically focuses on “the troops, the times and the technology.” These are honoured through carefully curated exhibits that educate and enlighten its visitors.

“You can read a story about World War Two – but reading does not provide the full picture. For example, our museum allows you to experience that history through objects – like Radio No. 33, also called the Maple Leaf radio, a set that weighs a hefty 630 lbs,” continues Annette. “Our museum allows you to experience that history through objects – like that radio. At the Military Communications and Electronics Museum, you get to see what soldiers wore and the equipment they used.”

“Obviously, we’re not on a battlefield, but the museum creates an experience, a snapshot that is worth a thousand words,” she explains.

At the Military Communications and Electronics Museum, the adventurous can step into the pages of Canadian history to discover the role that military communications and electronics have played in conflict and peacekeeping for more than a century.

Here, history comes to life.

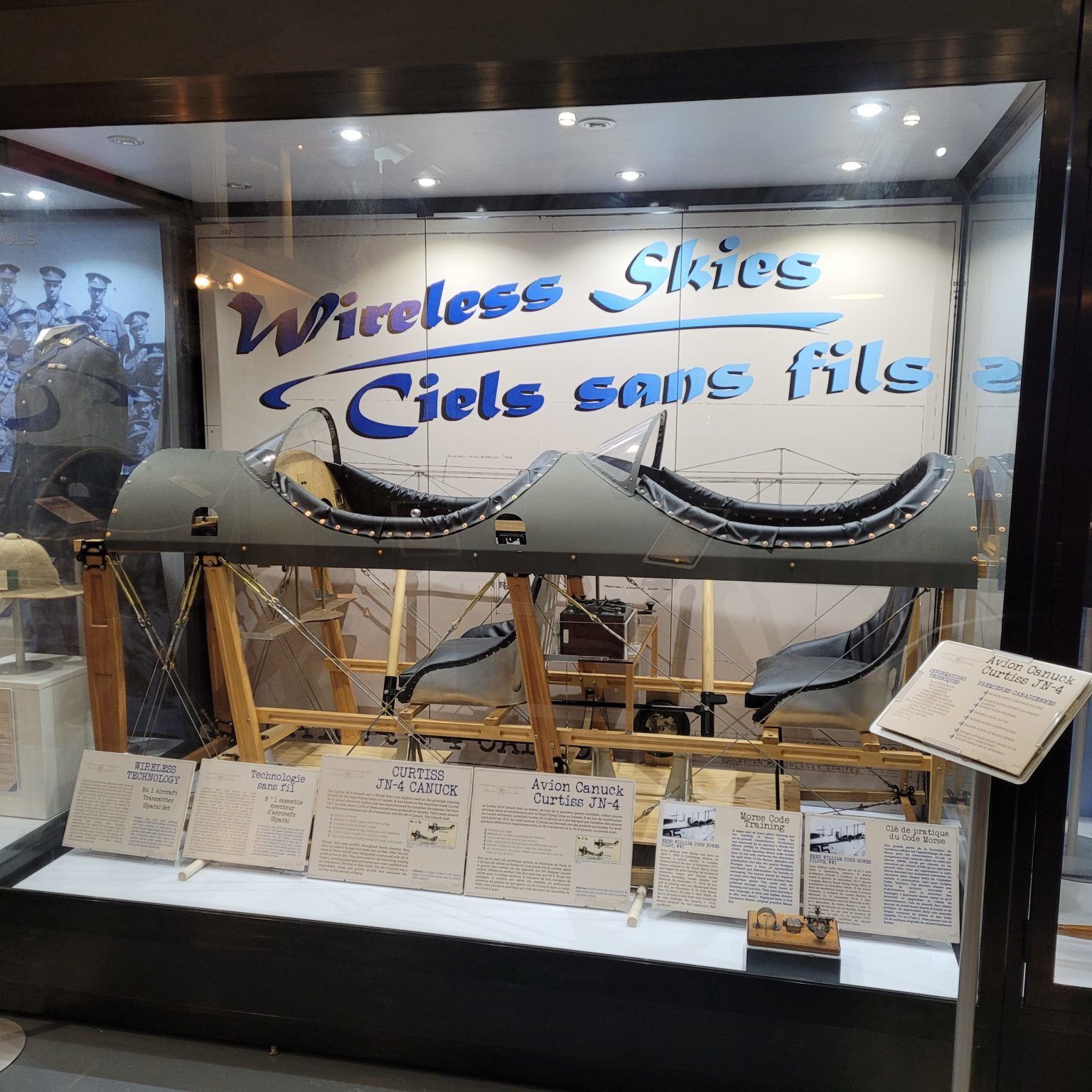

“The history of Telecommunications is a major part of the story for the Military Communications and Electronics Branch,” begins Annette. “One of the most prominent exhibits at the museum is the JN-4 Canuck display, which showcases the ingenuity and progress of military communication technology over centuries.”

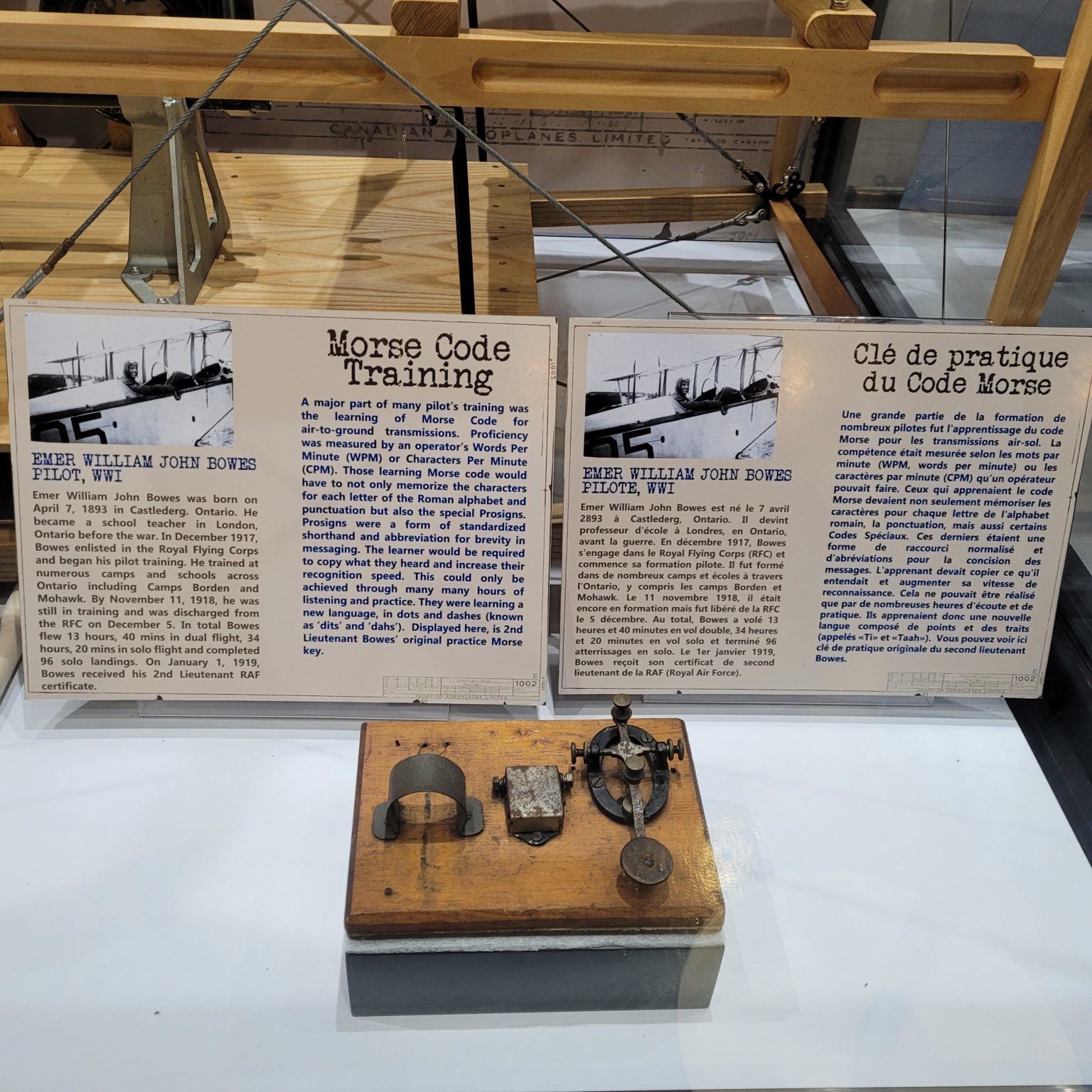

“Imagine it’s World War One and you’re trying to figure out: how can we communicate from the air to the ground, and send back information for reconnaissance? And due to the limited space in this airplane, you can either receive or you can send information. But then you see the scale of the JN-4 Canuck – and the scale of the radio, and you realize that it’s just so scary for a pilot and a passenger to share space with an engine and this radio.”

“It’s extraordinary – to showcase that scale to the visitor, and to realize that as early as 1915-16, we had the technology to gather reconnaissance from the air!” exclaims Annette.

The Military Communications and Electronics Museum is home to other celebrated and notorious communications technologies, including an Enigma Machine, cipher technology used by Nazi Germany during World War Two and Cold War-era equipment utilized by the Communication and Electronics Branch members active in NORAD’s underground fortresses.

Yet perhaps one of the museum’s most celebrated exhibits has little to do with communications and electronics, a testimonial to the impact of Canada on the world.

In the Vimy Memorial Room, the Military Communications and Electronics Museum houses Canada Bereft, the Grieving Lady and the Grieving Man, half-scale plaster models of an allegory of Canada’s immense sacrifice on European battlefields during World War One.

Created by famous Canadian sculptor Walter Seymour Allward, the figures of Canada Bereft guided the construction process of the Vimy Ridge Memorial in northern France, commemorating a battle considered to be a pivotal moment in Canada’s history as a young nation, a moment in time when the country emerged from Britain’s shadow.

“Canada Bereft is just breathtaking in the morning,” reflects Annette. “I love being here first thing in the morning when the sun casts light and shadow on her face framed by the ceramic poppies. To me, it’s one of the important displays that people must take in when they visit.”

The Military Communications and Electronics Museum doesn’t just show and tell – it also creates and curates experiences that challenge visitors to engage with history and explore their knowledge. Case in point: in partnership with Improbable Escapes, the museum has created Camp X and Spymaster, interactive games and mind puzzles that engage all five senses, plunging visitors into a world of intrigue, secrets, and coding, and turning them into wartime spies on a mission.

Camp X, explains Annette, was one of several dozen schools around the world that served the Special Operations Executive, located on the northwestern shore of Lake Ontario between Whitby and Oshawa in Ontario and created by the British agency in 1940 to promote sabotage and subversion behind enemy lines during World War II.

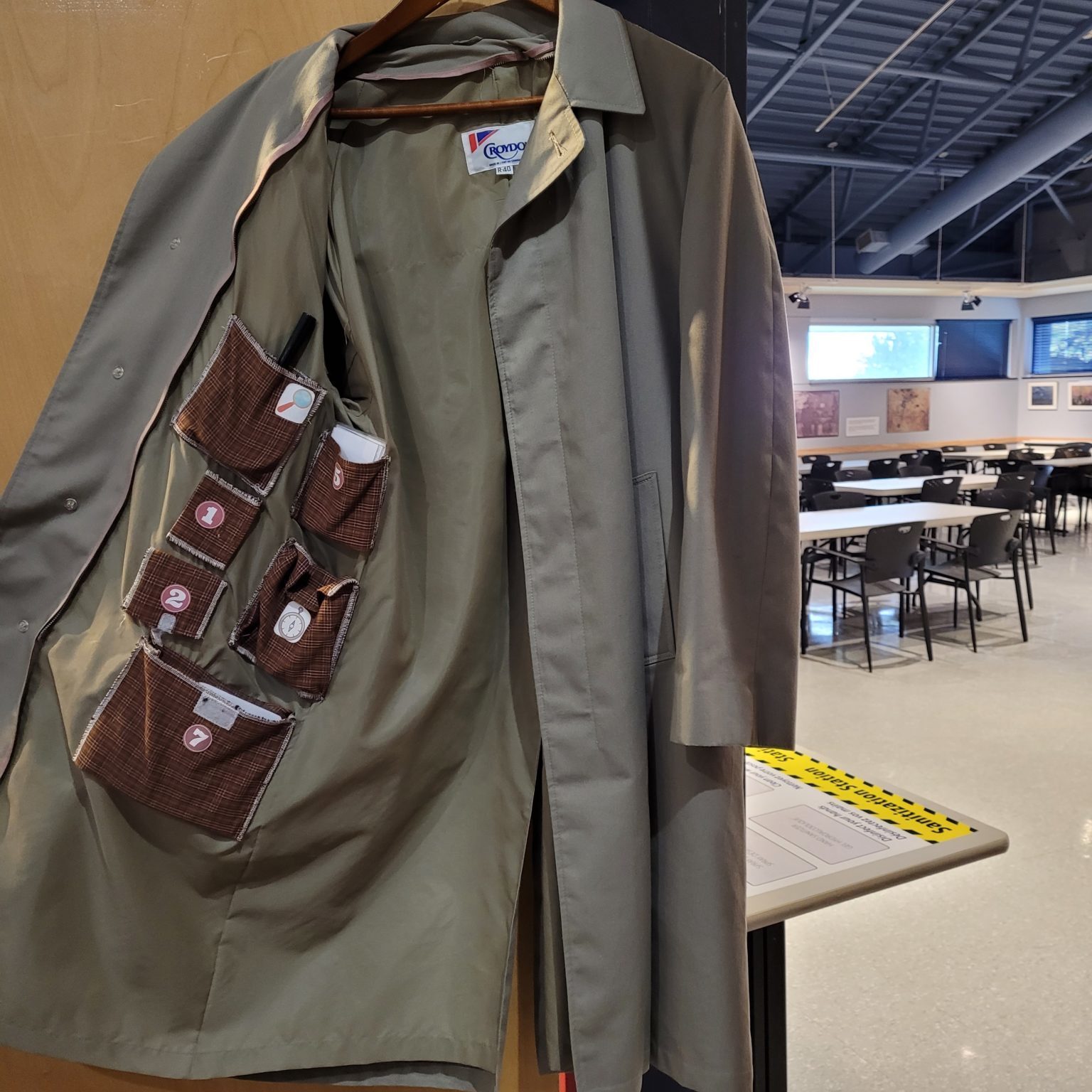

The game Camp X calls on visitors to don a trench coat, the pockets of which are stuffed with puzzles – crosswords, encoding and decoding tasks – inviting these would-be spies to engage with the gallery exhibits dedicated to Camp X to decipher clues.

“And because spies are pretty cool, we developed a game that’s a little bit harder called Spymaster,” says Annette. “This is where you’re an agent and you have to figure out who is the double agent, the traitor, that has turned on you. Similar to Camp X, there are a whole bunch of different little games, puzzles and clues you have to figure out. And during this game you are timed. Whoever completes the game first wins – and both these games are available to French-speaking visitors!”

While the Military Communications and Electronics Museum houses many exhibits in both of Canada’s official languages, Annette underscores that translating English-language exhibits to French has been a progressive journey – but that it is one the Museum is committed to seeing to completion.

“Our visitor is our motivator,” explains Annette. “We welcome many French-speaking visitors and there are many serving and retired members of our Branch and our community who are Francophone. To not provide as many exhibits as possible in the French language would be leaving out a huge part of our community.”

Translation of exhibits, key materials and the Military Communications and Electronics Museum website has not been without its challenges – but also, explains Annette, a powerful catalyst for insightful and unexpected revelations on military parlance.

“The military has its own culture – they have their own unique vocabulary and sometimes, the same word for an object or a concept might be used in both English and French. In fact, retired Francophone soldiers often laugh about it, because we are trying to take these historical terms and properly translate them to French – and they tell us, “We never would have called it that.”

Ultimately, achieving full translation to French also means honouring Francophones who have served in the Communications and Electronics Branch over the course of Canadian history, believes Annette.

“When you think about Morse Code, Teletype, these are all special languages and it’s a field of work that attracted people who were adept with language,” says Annette. “When we’re trying to tell the story of the people who are part of the Communications and Electronics Branch, a lot of them are Francophones.”

A treasure trove of history, technology, and innovation, the museum’s story unfolds itself to the visitor, its carefully curated exhibits and experiences shining a light on stories of ingenuity and imagination from Canada’s military past.

“We are such a niche museum,” concludes Annette. “And yet our audience is vast and incredibly diverse. We see military history buffs. Art majors. Archeologists. Tech nerds. Young and old. They want to come see radars, phones, switchboards – the Enigma Machine used by the Germans to communicate through codes during World War Two. The JN-4 Canuck. Canada Bereft.”

“And it’s all because our museum breathes life into history.”