Kingston was one of the earliest sites of European settlement and global immigration in Canada. The city has a history as a meeting place of Indigenous peoples and space for successful Black entrepreneurs. Beyond the bustling streets and modern facades of Kingston, many buildings have hidden stories dating back to the 19th century. Let’s take a journey to learn more about Kingston’s historic buildings.

216 Ontario St

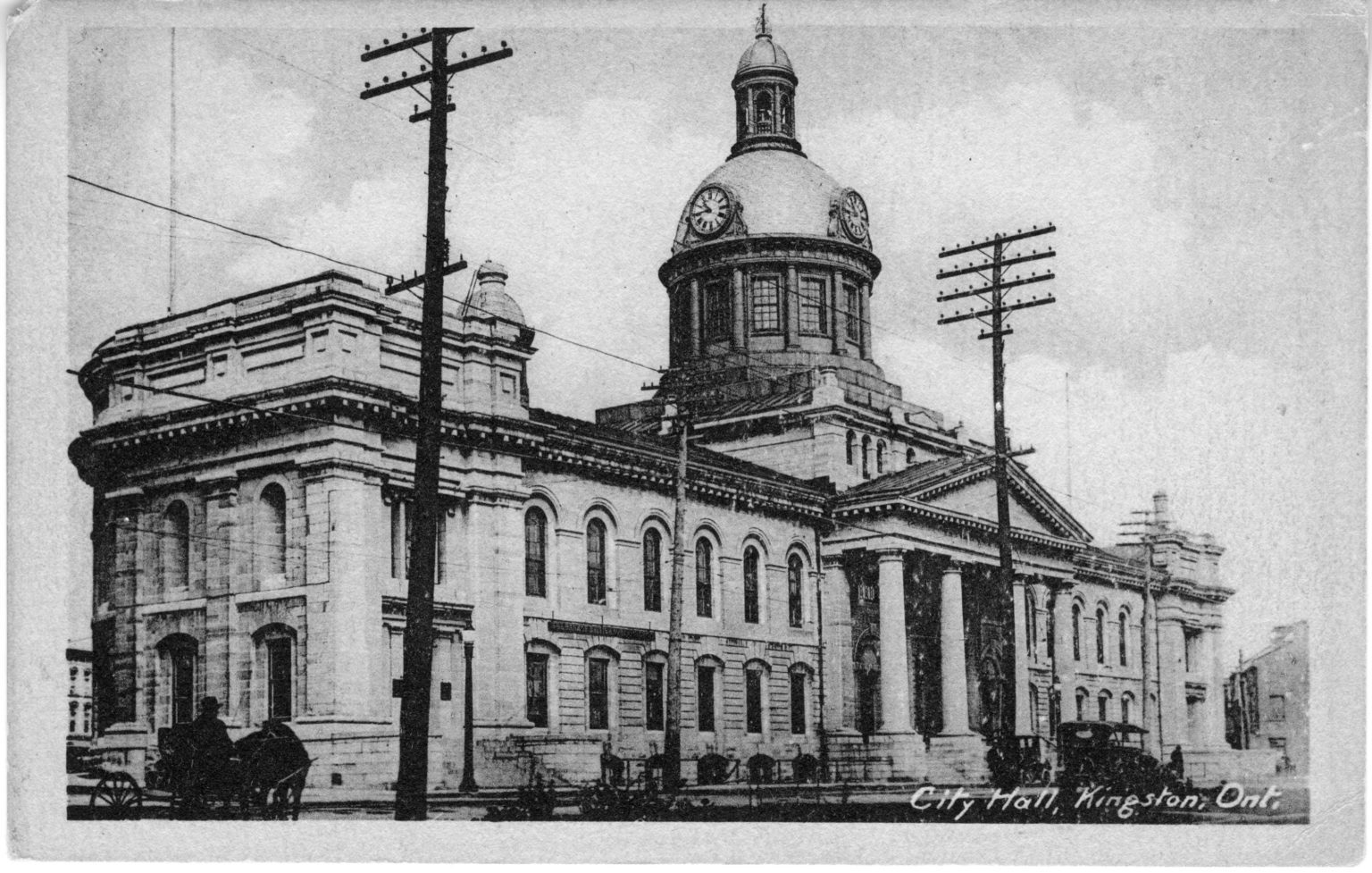

Kingston’s City Hall is a nationally designated heritage site and an iconic Kingston landmark. The architect George Browne designed and built the building in 1844 to be the space for a town hall and market. Although the building was meant to be a town hall, the space was rented out to many tenants. If you were to visit City Hall in the mid 1800s, you would find a bank, post office, theatre productions, courtrooms, church groups, and much more.

Two successful Black entrepreneurs, James and Maria Elder, operated Oregon Saloon in the building, a spot famous for serving oysters, fresh fruit, and wines. It was also home to Kingston’s original police headquarters until 1906, with working spaces for officers and dark basement cells for those who had been arrested.

Take a Guided City Hall Tour to learn more about City Hall’s fascinating history and beautiful architecture.

27 Princess St

Prior to housing Milestone’s restaurant and local office spaces, the Smith Robinson Building was known as the Commercial Mart. Built by architect George Browne in 1841, it became a space for Kingston’s many merchants. Between 1864 and 1940, a significant portion of this establishment was occupied by piano manufacturers Weber and Wormwith. The site housed The Kingston Vehicle Company, which specialized in the production and sale of buggies, spring wagons, and phaetons from 1894 to 1900.

During the Second World War, the Canadian military repurposed the property, using it as both barracks and a storage facility. Following the war, the building narrowly avoided demolition after the government’s declaration. Instead, it was sold to Percy Robinson and his brother-in-law Maurice Smith. Together they transformed it into the S&R Department store, which became a bustling retail hub until its closure in 2009.

120 Princess St

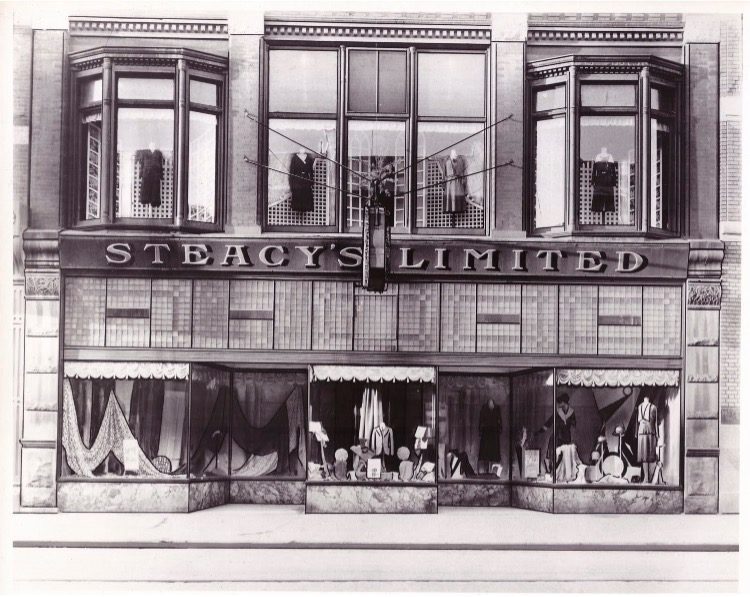

Back in the 1900s, if you strolled along Princess Street, you wouldn’t have encountered the glow of the movie lights from The Screening Room. Instead, your eyes would have been captivated by the exquisite displays of garments and merchandise at Steacy’s Department Store. Steacy’s made its move to 120 Princess Street after spending two decades at 106 Princess Street. From 1903 to 1983, visitors got to experience rides in the elevator with the elevator man, admire the glistening display cases, and savour the luxurious paper that encased Steacy’s products.

Following the closure of Steacy’s, it became home to Super Flicks & Food, a movie theatre offering second-run mainstream films at discounted rates and submarine sandwiches. Eventually, the theatre was renamed to The Screening Room, taking over the specialty/art house film niche.

Explore the film history of The Screening Room and other prominent locations on a self-guided walking tour.

209 Ontario St

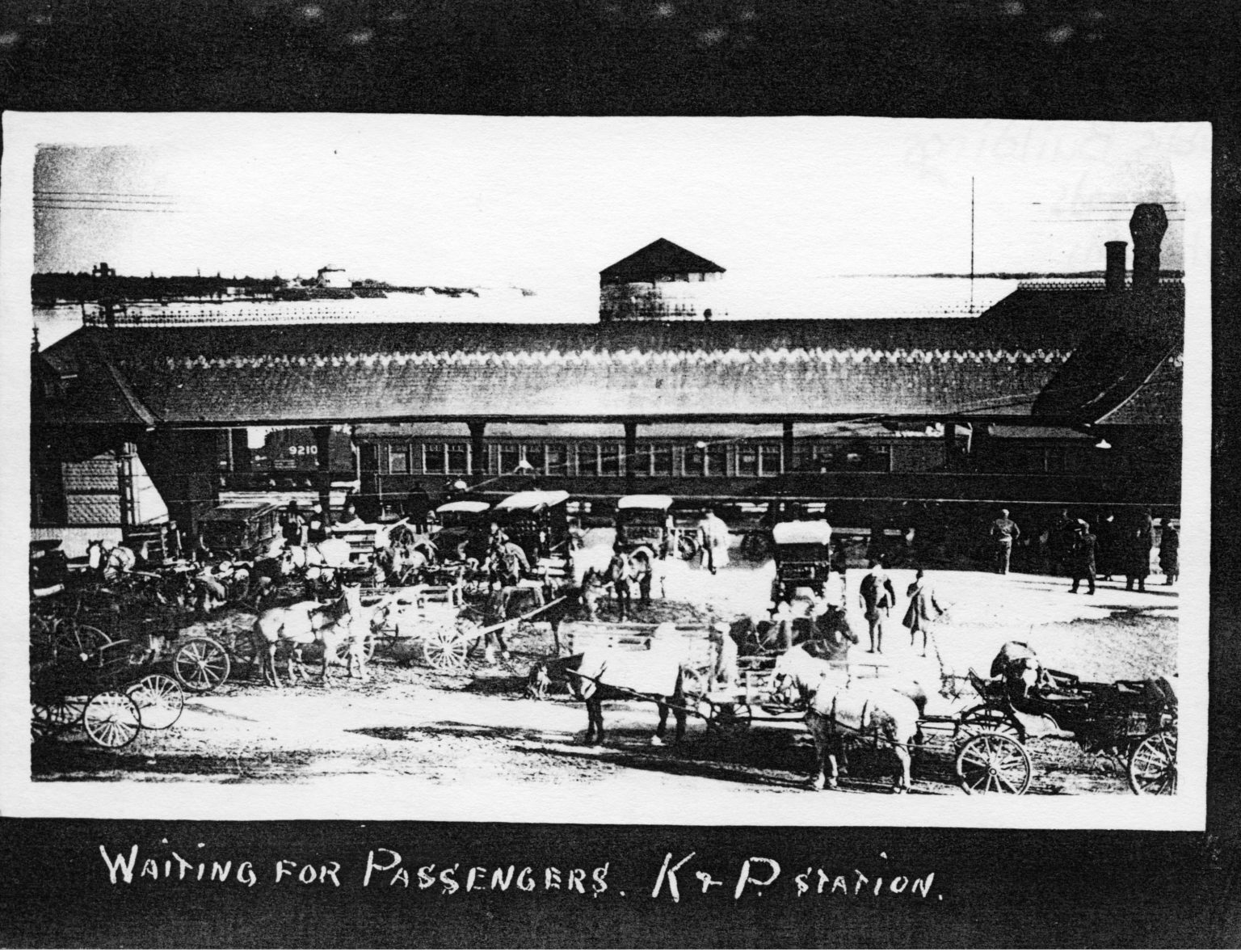

209 Ontario Street has been a gathering place for travellers since the construction of the Kingston and Pembroke Railway station in 1885. Also called the Inner Station, it was the southern terminal for the Kingston and Pembroke Railway (K&P), intended to run from Kingston to Pembroke. However, the railway only made it to Renfrew before it was terminated and the line was gradually abandoned beginning in the 1950s, with the last trains running in 1986. Now as the Visitor Information Centre, it is a space for visitors to make the most of their time in Kingston.

Check out Engine 1095, a locomotive built by the Canadian Locomotive Company once operating in Kingston, located behind the Visitor Information Centre.

218 Princess St

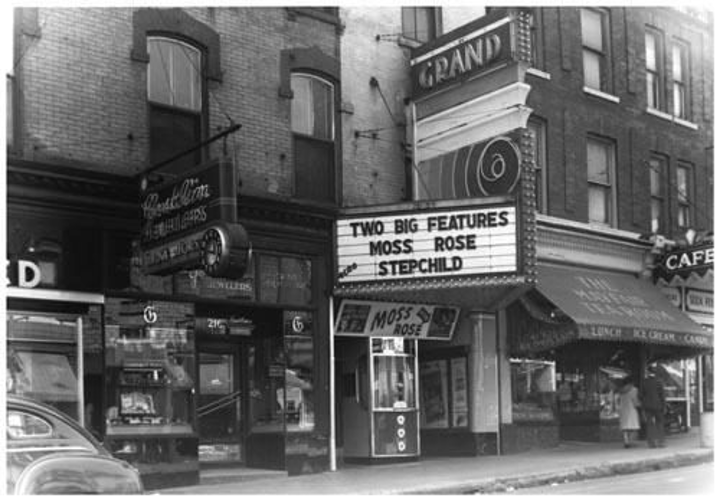

Originally, The Kingston Grand Theatre stood as the Grand Opera House, designed for live performances and constructed between 1901 and 1902. It was built on the grounds of the former Martin’s Opera House, which succumbed to fire in 1898. For several decades, The Grand operated as a movie theatre. In 1916, screened the controversial American film The Birth of a Nation (D.W. Griffith) with an orchestra and the 1928 silent World War I drama, Carry On Sergeant!

Since 1966, the building has been home to The Grand Theatre. It is one of the main performing arts venues in Kingston, featuring ballet, modern dance, theatre, comedies, musicals, film festivals, and concerts of all kinds.

To explore the music and film histories of the Kingston Grand Theatre, take a self-guided walking tour.

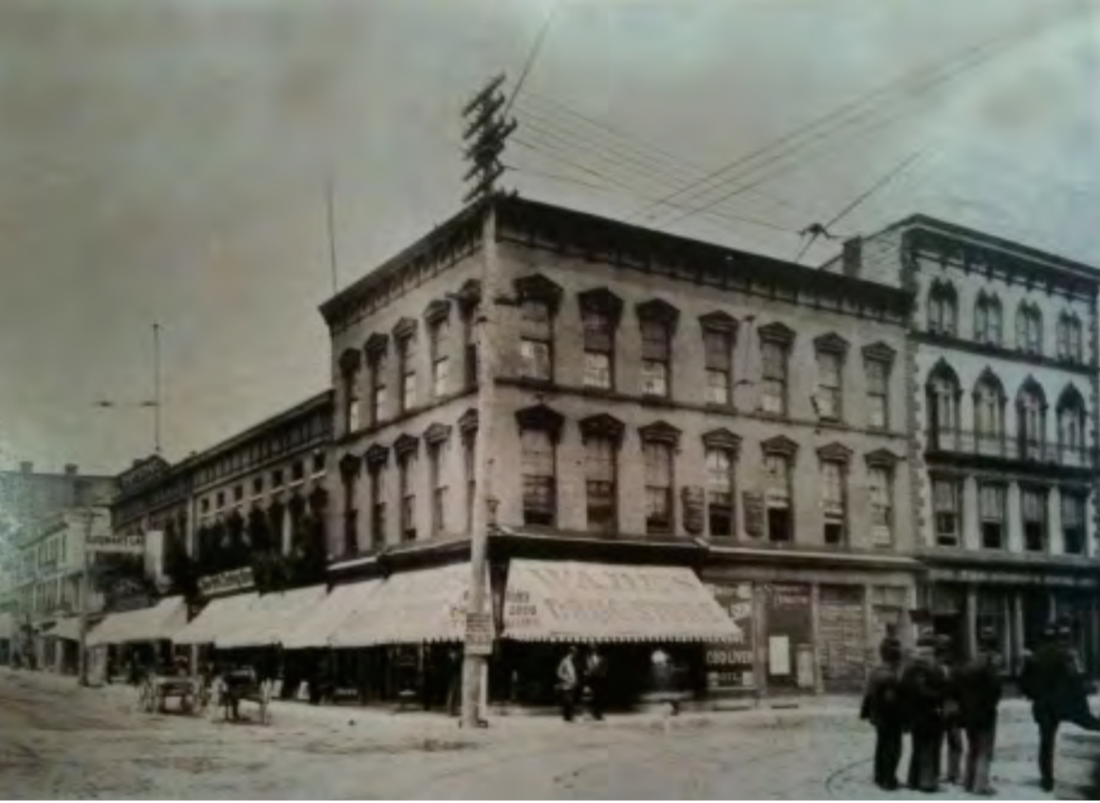

330 & 332 King St E

The northern corner of Brock Street and King Street, where Jack Astor’s now stands, boasts a rich history of thriving businesses. Among the notable figures associated with this location is William Johnson, one of Kingston’s earliest documented Black entrepreneurs. Back in the 1840s, his barber shop operated just two doors away from the corner on Brock Street on the north side of Market Square.

As time progressed, various businesses made their mark at this site. In the 1850s, it was home to the City Book Store, and in 1877, Wade’s Drug Store set up shop. Notably, in 1909, the building underwent a transformation, becoming the Bank of Toronto. Over the years, it has seen modern redesigns and updates, now serving as the location for Jack Astor’s, complete with an impressive rooftop patio overlooking Market Square.

200 Ontario St

Located adjacent to City Hall, the current site of Tir Nan Og pub once hosted a modest stone house, initially constructed in 1809 by Lawrence Herchmer. Over time, this dwelling was expanded to incorporate a store, catering to the needs of travelers arriving in the city. Subsequently, it evolved into a bustling center for shops and warehouses. During this time, the Elders operated the Oregon Saloon within the premises. Eventually, the property changed hands, finding its way into the possession of merchant William Henry Alexander.

After a destructive fire in 1848, Alexander initiated the reconstruction of the building. He enlisted the services of Kingston architect William Coverdale. The revamped structure was transformed into a hotel and underwent several name changes, including the Albion, Stanley House, Brown’s, and the Iroquois. However, in 1918, it assumed its enduring identity as the Prince George Hotel. Today, as you stroll by, you can still spot the original Prince George Hotel sign.

For a deeper exploration of Kingston’s buildings and the diverse individuals who have called these spaces home, visit Stones Kingston. And check out Tracing Kingston’s Solidarities, a series of performance pop-ups in Springer Market Square on October 20-21 and November 3-4 to activate Kingston’s hidden Black histories.